Herein you’ll find articles on a very wide variety of topics about technology in the consumer space (mostly) and items of personal interest to me. I have also participated in and created several podcasts most notably Pragmatic and Causality and all of my podcasts can be found at The Engineered Network.

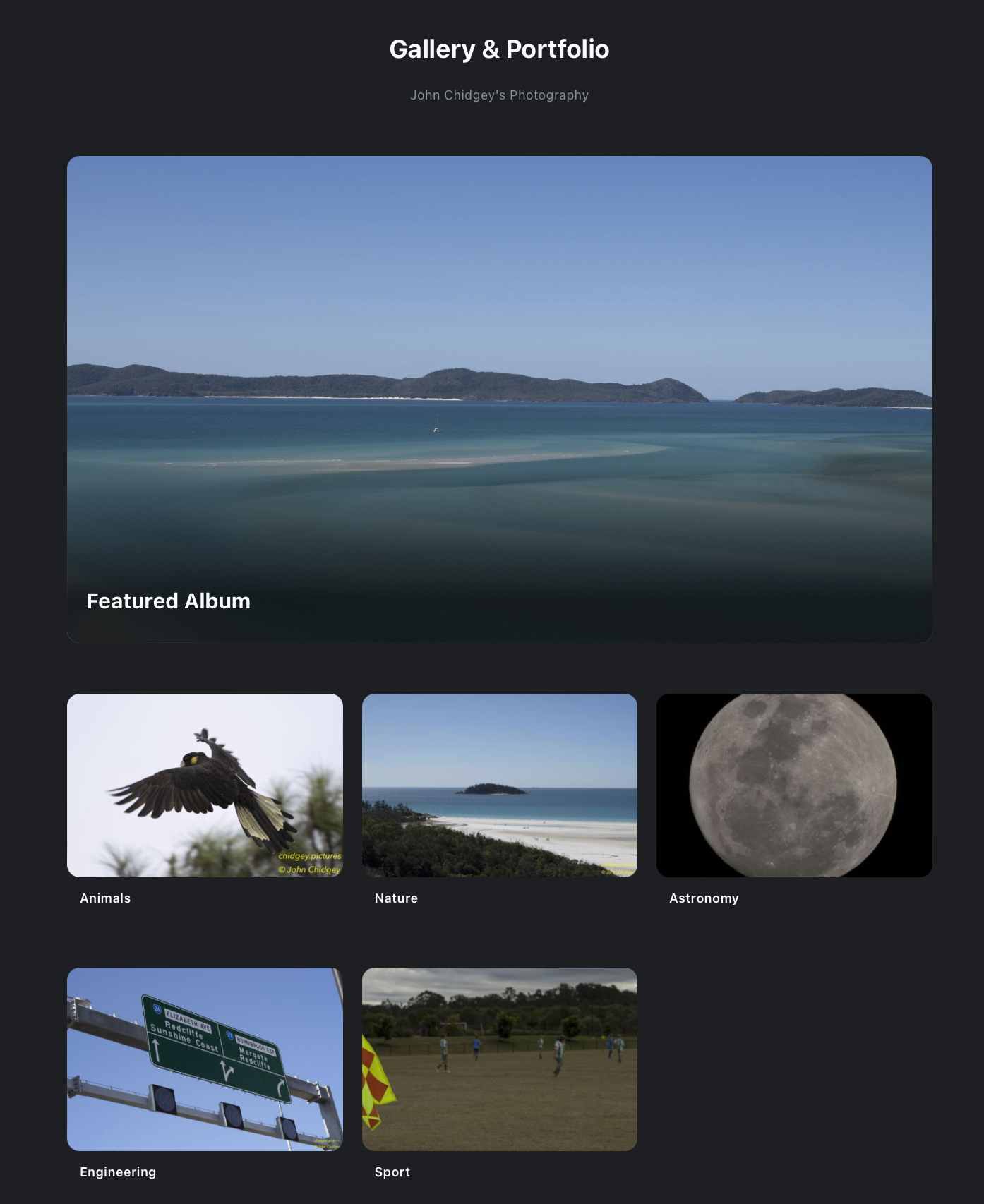

Introducing: Chidgey.Pictures

During the COVID19 pandemic in mid-2020 I dissolved my PixelFed instance and moved all of my photography to TechDistortion. Since then I’ve taken many more photos but the structure of this site for Photography specifically felt very clunky. I’ve been searching for a new site template and finally found almost exactly what I was looking for!

As of today all of my photography can now be found at https://chidgey.pictures. Existing links should re-direct as well.

The layout is much cleaner with photos groups and classified into a more traditional portfolio style making it easy to track down favourites. I’ve also removed a lot of the cruft and reintroduced watermarks.

For now it’s a content clone of the existing portfolio but in time I’ll start adding new shots as I sort through my backlog.

Enjoy!

Fact vs Truth AI Edition

The digital world is undergoing a major revolution: Machine Learning or ML (a subset of Artificial Intelligence or AI) is being used increasingly in our digital world. There are many applications such as for image recognition or voice recognition, meaning the AI model is interpreting or ingesting information and providing an attempted description of that content. This allows people access to subtitles (for the hearing-impaired) or makes it easier to track down that photo in your library you just can’t find.

What happens though when these interpretations are turned around into advice, to direction, to action? In particular, recent advancements in Generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) are pushing traditional search engines to reconsider what’s possible. Google have led the Search Engine business for decades with more than 90% of global search volume representing a monopolistic market dominance in that space. Hence when Google announces changes to their search engine, the technology world pays very close attention.

A few weeks ago Google announced at their annual conference that they were intending to gradually introduce Generative AI search results based on their Gemini AI, to their standard web search engine, calling it AI Overviews and launching it in the USA initially, with other countries to follow in coming months.

In a move similar to the iconic “I’m feeling lucky” button, that will take you straight to the top search result answer rather than letting you read and select the one that fits best yourself, AI Overviews will present its response to your question with no links to external sites required to be followed, should you wish to just trust its response.

Of course you can follow links further down the page to clarify the answer, but to those that genuinely aren’t interested in digging for themselves, it’s easy to simply take the response on face value.

People are going to be people, and if something like AI Overviews exists people are going to poke it, and poke it, and poke it, until it breaks. It didn’t take long either. Examples began cropping up on social media of search examples that suggested adding Glue to Pizza Cheese to stop it sliding off the pizza, mixing Bleach and Vinegar to clean a washing machine (that would make Chlorine Gas…see below…), and that eating a rock a day might keep the doctor away. There are many, many more examples but that’s a small sample.

To a human, two out of three of these examples above are obviously ridiculous, however the Chlorine Gas example is not necessarily so obvious for those not familiar with chemistry. Whilst I personally know that the active ingredient in bleach is Sodium Hypochlorite (NaClO), Vinegar is Acetic Acid (C2H4O2) and if you mix Hypo with an Acid it will liberate the Chlorine Gas in that chemical reaction. Many people don’t know this. It may sound reasonable to some people and they may attempt it without a second thought with potentially deadly consequences if this is done in an enclosed space, with little to no ventilation.

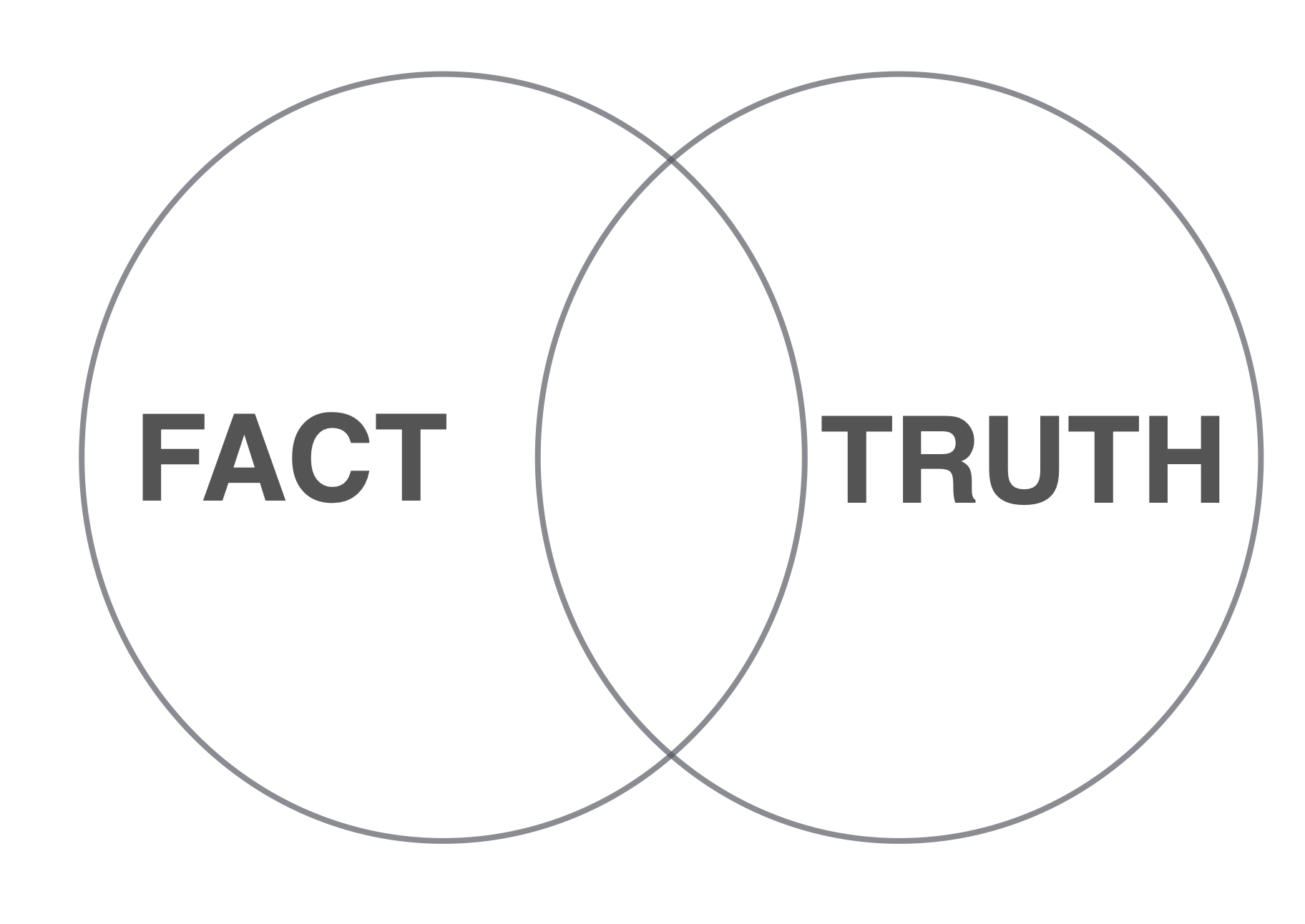

The problem is that ML of this kind is attempting to provide Facts, but in reality it can only ever realistically, provide Truths. To understand what I mean, we need to refresh ourselves on the differences between these two things. The dictionary definitions of each offer some help in differentiating Truth vs Fact, with the following extracted from the Oxford Dictionary’s attempt:

- Truth: the quality or state of being based on fact; a fact that is believed by most people to be true.

- Fact: a thing that is known to be true, especially when it can be proved.

To paraphrase then, “Facts” are things that can be proven and “Truths” are things that are based on the majority belief (opinion) that may or may not be provable. Hence in a Venn diagram Truths can contains Facts, but there are Facts that may not be believed by the majority and are thus not considered to be Truths. The ideal position is the overlap point where Facts are believed by the majority and are also therefore considered to be Truths. The size of this overlap is highly variable and flexible over time depending upon the topic in question.

That’s nice, you say, so what’s the big deal? Well…all ML models are only as good as their input or training data. The old adage of “Garbage in…garbage out” applies. Ensuring the quality of input data has been an age-old problem that highly trusted publications like the Encyclopaedia Britannica have been grappling with since its inception in 1798. In many way EB was the worlds first large-scale attempt to capture factually provable information on a broad range of topics.

They relied on researchers interviewing and investigating their entries and cross-checking wherever possible with significant emphasis on information from credible sources. Whilst Wikipedia can be useful for quickly tracking down high-level information on many topics, its collaborative model allows for rapid changes that aren’t necessarily referenced (citation needed) which creates a maintenance burden for those wishing to have content corrected.

Real-life subject matter experts and even those directly discussed in Wikipedia articles find themselves unable to have errors corrected. The rate at which un-cited or factually incorrect information can be added, far exceeds the rate at which Subject Matter Experts can rectify it, due to its open nature. Unlike EB (as an example) that has an Editorial bottleneck to prevent incorrect information from easily entering, Wikipedia does not have this. As such most scholarly organisations do not permit linking to Wikipedia, whereas linking to EB or more controlled information sources, is generally more accepted.

The only potentially sensible path to take is the flagging of input content into AI models that has Meta-data that identifies its quality, factuality, or trustworthiness. How one determines this score or criteria is highly subjective and prone to influence from human biases that mutate over time, can be based on current micro/macro societal trends and such, but assuming this is even possible could you encode information with a watermark or traceable identifier that it came from a human? A factually accurate source?

Irrespective of the technical solution for how this could be accomplished, the far better question is, what is the incentive for content creators to add such meta-data legitimately and then what is the punishment for not, or for mis-encoding it, assuming the difference can be reliably detected? Just because data was created and entered by a human doesn’t mean it’s accurate, factual or even sensible. It could be gas-lighting, trolling, a mis-understanding or basic ignorance. If one was running a spamming server-farm operation designed to pollute the world with mis-information for a price to the highest bidder, then why would/should they flag their data correctly?

Wikipedia is however a balance and counterbalance system such that, if we add disruptive information, there is an opportunity to correct the imbalance..albeit potentially slowly. Too many people take Wikipedia on face value as fact, when it is closer to a Truth than to a Fact in many cases. What happens when people start to take Google Search’s AI Overviews as Fact, rather than as a Truth? Individuals are not so freely able to provide feedback input as they are for Wikipedia and if they do, can it be trusted?

Let’s say that a human makes a website, YouTube or TikTok video with information that was guided by Generative AI content, which then is re-ingested by the AI model. Over time this then adds reinforced incorrect information into the AI model which then further provides incorrect responses for still others to potentially believe.

This pattern is no different to existing Human conditions, sometimes referred to as Urban Legends, or more traditionally the term used was folklore.

Before the internet, small groups of people could believe a Truth without external validation. This is as true today as it was thousands of years ago. Even for insular online communities, this is still prevalent today. This is in many ways, nothing new.

We have turned to the Internet and technology to create a body of knowledge that is unsurpassed in all of human history for people to turn to, for answers to questions ranging from the trivial to the life-threatening. However with AI now able to amplify factually incorrect information at a more rapid pace than ever before and many people seemingly willing to believe what it says, will these tools just become the ultimate Random, Unintentional Gas-Lighting mechanism for factually incorrect information in our history?

There is so much buzz surrounding the use of ML in this way and yet no matter how I look at it, I can’t see how this is a solvable problem. On an individual level it will come back to trust, and it’s hard to look into a future where people simply start trusting, blindly, what the ML spits out.

Perhaps we should return to word of mouth? Return to trusting professionals that have studied and practiced for decades in fields of construction, telecommunications, plumbing, electrical wiring, laying bricks, making pizza even, and anything else for that matter, rather than asking a search engine or watching a YouTube video looking for a quick and easy answer to a question.

Maybe it’s better to return to reading up on materials from multiple sources, books, papers, talking to people and making up our own minds rather than leaning on automated systems to do the thinking for us in hope of saving a few minutes. There is no substitute for taking the time, making the effort, educating yourself and thinking it through. There never will be either.

Some decisions you need to seek the right answers and to ask the right people, and stop pretending the internet can give you the right answer for everything, every time. It can’t now, it never could, and it never will.

Treat AI responses the same way you treat a door to door salesperson: with a large dose of skepticism and some weary caution.

There are many applications where AI/ML can be beneficial to humankind. This though, just isn’t one of them.

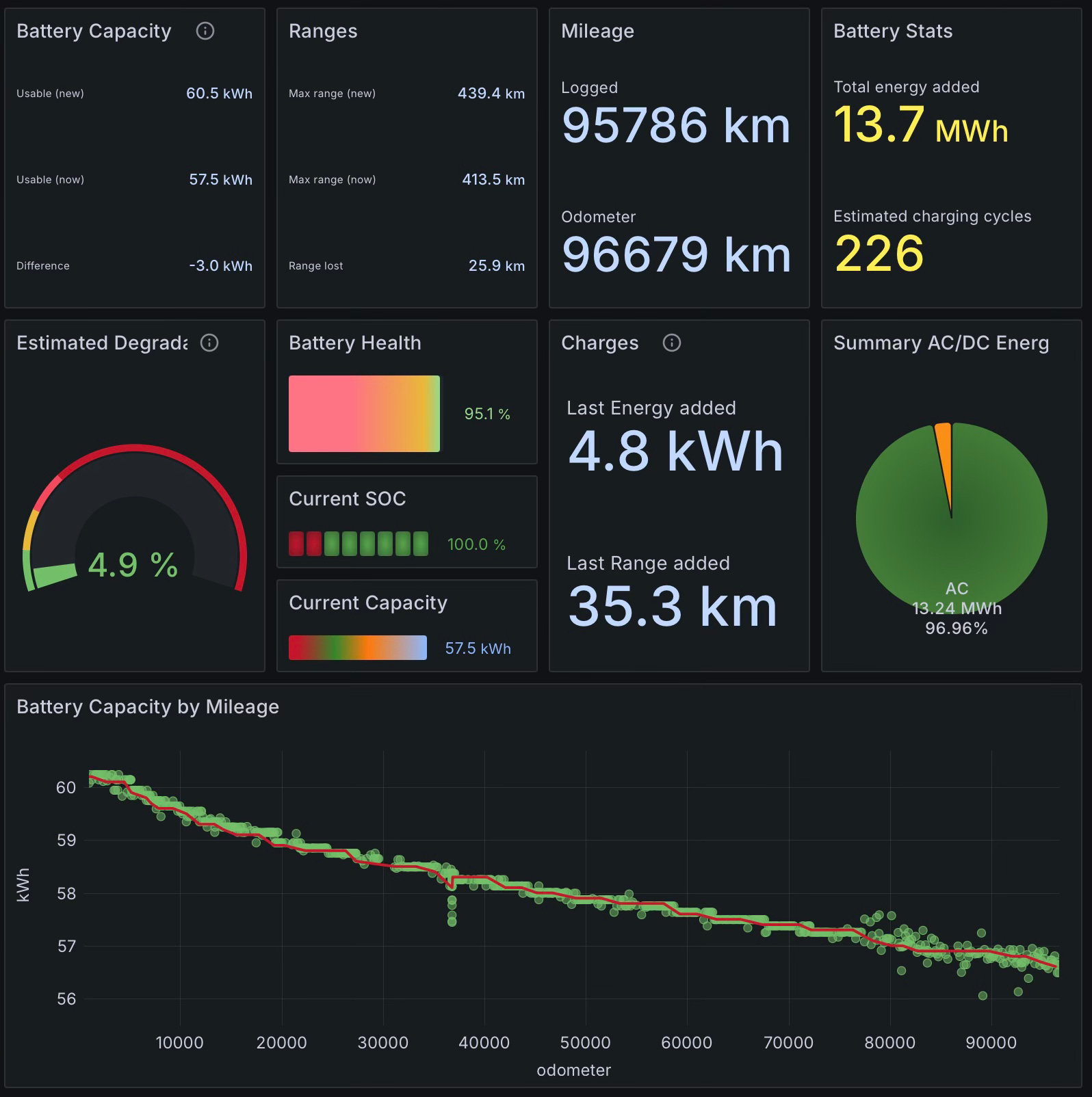

You Convinced Me Not To Buy A Tesla

…Or any other Electric Car…or at least, that’s what one of my co-workers told me last week. We’d been discussing the state of new cars, how expensive they’ve become and the pros and cons of electric cars. Being the only person in the room to own both a Battery Electric Vehicle and a Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle, I mentioned my battery degradation statistics for the Tesla Model 3. It’s now approaching 3 years old and has almost clocked up an even 100,000 kilometres (62,000mi) and I’ve been tracking the car using my own Teslamate instance for almost that entire duration.

In a recent update the Teslamate Dashboard list had added a new Battery Capacity display that was specifically tailored for those owners with LFP Battery chemistries, like my car has.

When I told the group my car had only lost 5% of its range in the last 100,000k’s they were a mixture of, “shrug, whatever” and aghast. “My ICE Car still has the same range as when I bought it and I’ve run it for twice that distance!” said one of them.

The average lifespan of a petrol engine is about 300,000k (~200,000mi) before it needs either reconditioning or replacement. Practically no Diesel engines are naturally aspirated anymore and adding a Turbo-charger shortens the lifespan of a diesel but they’re still better than petrol regularly reaching 500,000k (~300,000mi).

Quotes vary from car to car and engine size and type as well, but a recent polling of sites averages between $4k-$5K AUD to recondition an engine of either type. For those unaware, reconditioning involves reboring the cylinders in the engine block, upsizing the pistons/rings and after a few adjustments…away we go.

Reconditioned engines won’t last quite as long as the original and some modern engines can’t survive a second rebore as the wall thickness of modern engines aren’t as chunky as they used to be. That said, you can go for a second or third time but it depends on the engine and how bad the rebore was. Each time you do this you lose some efficiency but get to keep the car. Failing rebores you could replace the engine but that’s subject to finding a suitable replacement.

I once drove a car with 300,000k on the clock and gradually at first, then at an alarming rate the engine started losing power as it crossed 320,000k and then finally would barely move at 330,000k. The engine simply couldn’t hold compression. It was a company vehicle and the owner opted to sell it for scrap.

To summarise I don’t agree with the mentality of the person that said, “You convinced me not to buy a Tesla…” (or any Electric Vehicle) due to battery degradation. How’s that exactly?

The rate of battery degradation for LFPs is known to be relatively linear, hence projecting forward assuming 100,000k/3 years and 5% loss per 100,000k and let’s say any range less than 200klm makes the car unusable, it will take approximately 30 years before the Tesla becomes “unusable” by that metric, although it would still be fine for a daily commute for myself personally, even with that range. That would put the clock at 1 million kilometres (620,000mi) for which a petrol car would need two reconditions during that time and third to keep running beyond that.

If a new LFP battery still costs $22,000 AUD in 30 years I’ll be shocked, but given that 80% of that cost is the battery itself and the rest is labour, it’s fair to say it will have dropped below $15,000 AUD in total by then, judging by the cost/kWh for LFP batteries over the past five years alone, and graciously assuming a flattening of cost in 20 years time. At worst this is effectively the same equivalent cost of ownership as an equivalent petrol ICE vehicle, and unlike an ICE vehicle an EV is still perfectly drivable the whole time.

For the record I went though all of this detail with the person in question, but I think it comes down to a different way of thinking about the problem. Electric Cars are the immediate future for vehicles and they will mostly displace ICE vehicles, but it’s going to take some time for some people that are deeply entrenched in the “that’s just the way it is” mindset about what vehicle cost of ownership must be, before they can embrace what it can be.

Anti-Trust

On the 21st of March, 2024 the United States Department of Justice (DoJ) brought an Anti-Trust lawsuit against Apple, with their complaint shown here with some excerpts as follows:

Unless Apple’s anticompetitive and exclusionary conduct is stopped, it will likely extend and entrench its iPhone monopoly to other markets and parts of the economy…

This case is about freeing smartphone markets from Apple’s anticompetitive and exclusionary conduct and restoring competition to lower smartphone prices for consumers, reducing fees for developers, and preserving innovation for the future.

By maintaining its monopoly over smartphones, Apple is able to harm consumers in a wide variety of additional ways

Whilst there are a great many statements that are factually incorrect and misleading in the DoJ submission, the important issue of question for me initially is simply: by the definition of a Monopoly under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in the USA, does Apple qualify as a Monopoly at all over smartphones in any dimension?

The summary of what the Act interprets as a Monopoly can be found here but this is the key sentence:

An unlawful monopoly exists when one firm has market power for a product or service, and it has obtained or maintained that market power, not through competition on the merits, but because the firm has suppressed competition by engaging in anticompetitive conduct.

The wording is clumsy, so let’s work this through. If a “Product” is meant literally in the singular sense, a single widget, made identically, from a single supplier under the same name, certified as such by that manufacturer then every widget is a monopoly within itself. If we interpret a “Product” as meaning a “Product Class” or a “Product Type” or perhaps a “Product Category” then if we had widgets of similar functionality and similar design, but supplied by multiple companies that leads to choice for consumers, that is the outcome that we want. If Company A that makes Widget A, finds a way to limit the production of competing products of the same product type, but from other manufacturers, then that could represent a restraint of trade and shows monopolistic behaviour.

Therefore we can only reasonably interpret “Product” in this context as a “Product Type” and the DoJs use of the phrase “iPhone Monopoly” is a non-sequitur and what they meant to say (as they did later in their document) is “Smartphone Monopoly”.

Similarly “Service” can be more correctly interpreted as a “Service Type” and in the context of Smartphones this could include Text or Multi-media Messaging Services, EMail etc.

Next question is does Apple have a Monopoly over Smartphones as the DoJ assert? Globally Canalys showed Apple in Q1 of 2023 behind Samsung and the longer term analysis here suggests that Samsung alone beat Apple in Smartphone sales in 6 out of the 8 quarters in 2022 and 2023.

However since the DoJ is USA focussed Canalys also reported that in the United States in Q3 of 2023 Apples market share had dropped year over year from 57% to 55% by shipments.1

If Apple’s marketshare is actually about 20% of global smartphones and just over 50% in the US, then can Apple reasonably be expected to have Market Power over the others? Certainly not in the smartphone hardware, but what about the software? In the context of smartphone operating systems, iOS only runs on iPhones (Apple’s only Smartphone). However reflecting on the attempted Anti-Trust Lawsuit against Microsoft with 9 out of 10 computers coming with Microsoft Windows pre-installed at that point in history, Microsoft had a monopoly over the operating system, not the computers themselves.

The better question then is what operating system in the smartphone context is similar to that of the personal computer context of the 90s and 00s. This analysis suggests that Android is maintaining 75-80% marketshare globally, and 40% and growing in the US, with iOS only getting over 20% globally three times in 8 quarters, and about 50% and dropping in the US.

So What?

The problem with this Anti-Trust case is that the wording used and referencing the Act as it stands, will simply lose. Apple is not a monopoly in that sense and if the DoJ were actually interested in smartphone monopolies (globally) they should have gone after Android, although the ownership of Android is rather complicated by Googles design.

What the DoJ Meant To Say

It’s unavailing at this point in time to chide the DoJ for such a poorly understood or written submission against Apple. If I were to extrapolate what they meant to say though, it would be something like this:

All smartphones and personal computers shall be open to install and run applications (apps) at the discretion of the owner and user of the hardware in question.

The fascinating point is that Apple have a split philosophy that’s been talked about for years: on the Mac you can install anything from anyone (though recently SIP, Gatekeeper etc have added more warnings to users about risks of so doing), whereas on iOS devices you can not. Apple cite a litany of reasons to justify their restrictiveness on iOS but it really doesn’t matter what those reasons are anymore for one reason alone: ubiquity has led to reliance.

The Platform Lifecycle

The word “Platform” is intentionally generic since you could argue that the platform for Railroads a hundred years ago was an engine pulling carriages on an agreed width of rails to move people and goods around the country. In this context the Mobile Phone was a platform for voice calling other people and was an extension of the Telephone system. The Smartphone was a platform for transferring information between people and the internet.

Of course you can iterate down that technology stack and identify that the Internet is a platform, as is the landline phone network, as is the mobile phone network.

Each of these platforms have approximately followed the stages of their lifecycle below:

- Invention

- Early adoption

- Competition

- Ubiquity

- Reliance

- Regulation

In the case of railroads in many countries, once technology was invented it was adopted by one company to fund construction of the first rail lines as they identified money could be made. Then more companies built more lines and in some cases governments built some infrastructure as well, with the companies then competing on price. Once rail lines were widespread they had become ubiquitous with practically every town touched by a rail line and station. With this came more commerce and more people began to depend on them for food deliveries, mail, and to get around and the majority of the population came to rely on them.

At this point there were problems in some countries including the United States where one company owned a rail bridge and restricted its competitors from using it. The reliance and pressure from end users forced more regulation into place to prevent monopolistic behaviour from continuing.

In the smartphone market it’s been a similar journey so far, with smartphones now crossing beyond ubiquity into reliance. Why do I say that? Have we become reliant/dependent upon the smartphone? With some online services a smartphone is required for multi-factor authentication to log in. In some businesses contracts require specific messaging apps, based on smartphone platforms only, to stay in touch as part of the job. In some countries, governments are moving away from physical identification to digital identification, held on your smartphone.

Credit and Debit physical cards are becoming less common with the advent of more convenient technologies leveraging PayWave and PayPass such as Google Pay and Apple Pay. Some online banks don’t issue physical cards by default anymore. Finally there are many people that own a smartphone that don’t own a computer, whether that’s a desktop or a laptop computer, simply because smartphones are smaller and cheaper.

With many forms, applications and such today, it’s only possible to fill these in via a web-form which requires a computer or a smartphone, hence the smartphone has indirectly become the required tool for this purpose. Given that they’re being relied upon now, we start down the road of regulation.

It was inevitable.

Was Anti-Trust the Right Approach?

No. Apple does NOT have a monopoly or market power in the smartphone platform space. The better approach would be to follow in the European Union’s footsteps with the Digital Markets Act. Regulation is required but it must equally apply to all entrants in the Market - NOT JUST APPLE.

The interesting question though is that if you’re the inventor of a technology and you can set the design direction from day one, would you do that in the knowledge that in the future, if your technology becomes a ubiquitous platform that is relied upon by the majority of the population, you will be forced to do things against your original design direction by regulation?

Since the smartphone was created about 25 years ago (debates over who invented the first one notwithstanding) then that’s up to two and a half decades of mostly, do-what-you-want until you face regulation.

Maybe that head-start is enough…depending on your point of view of course.

Whether or not the AntiTrust case against Apple goes anywhere useful, it will be followed by more legislation. The DMA will be enforced even more harshly until Apple and other technology companies get the message. The user owns their own device, not Apple, and the user should be free to choose how they want to use it.

-

Updated 16/4/24 to split out US Market Share and Global Market Share to focus on DoJ’s direct remit. The conclusion doesn’t change. ↩︎